When Hurricane Iniki struck Kauai in 1992, the scale of community giving became known as the Iniki Effect.

When the Challenger rocket disaster of 1986 took the life of astronaut Ellison Onizuka of Kona, the pain of loss resulted in a scholarship fund that continues to support Hawai‘i students through college.

When the East Japan earthquake and tidal wave struck in 2011, children by the thousands joined their families in contributing to the relief drive.

When Violet Loo was a little girl in Singapore, she watched her famous father, the filmmaker Run Run Shaw, distribute rice to the aged and poor at New Year. After migrating to Hawai‘i, she founded the Paul and Vi Loo Theater at Hawaii Loa College.

When Dwayne Steele was a little boy growing up in Kansas, he could not have imagined he would become “Nakila” Steele in his adopted Hawai‘i, the quiet benefactor of a community school dedicated to perpetuating the traditional Hawaiian dialect of remote Ni’ihau.

SUCH STORIES share what seems to be a nearly universal impulse to give to a common good. According to a survey by the HAWAII COMMUNITY FOUNDATION, ninety-three percent of all Hawaii households engage in some form of giving, and nearly two-thirds give money.

The results of giving are all around us, yet the practice of giving goes largely unremarked, often intentionally. Kahiau Foundation “gives from the heart with no expectation of return.” Recently it gave a major grant to build a community kitchen in Papakolea.

King Kamehameha

We might argue over what constitutes philanthropy, but the themes of community-building, compassion, and inclusiveness would recur. The founding figure of a united Hawaii, Kamehameha I, set a standard of equal treatment for the mighty and the weak. “Respect alike men great (kanaka nui) and humble (iki),” he famously proclaimed. “See to it that our aged, our women and our children, lie down by the roadside (in their travels) without fear of harm.”

Hawaiian hula dancers in the 1890s, Hawaii State Archives via Wikimedia Commons

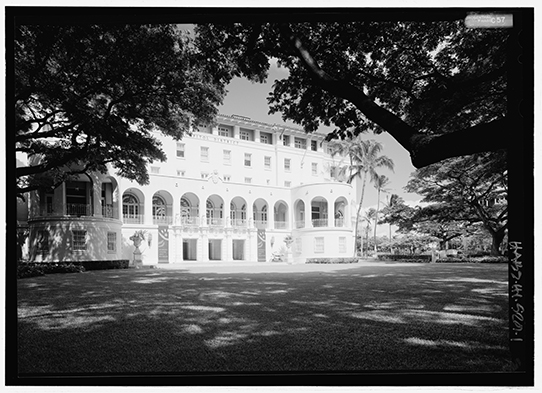

The HAWAII OF KAMEHAMEHA was confronted with the devastating impact of contact with the outside world. Epidemics of previously unknown diseases, such as smallpox and measles, set the stage for our historical definition of philanthropy. Where the high alii and the monarchs of the Hawaiian Kingdom might have passed their assets to family members or retainers, they instead addressed their resources to health care, child care, education, and support of the elderly. For example, Queen Emma, in collaboration with her husband Kamehameha IV, raised the initial funds to launch the present-day QUEEN'S HOSPITAL (1860). William Lunalilo, the sixth Hawaiian monarch, willed lands for the creation of LUNALILO HOME for the elderly (1877). Queen Kapiolani, wife of the seventh monarch, Kalākaua, raised the startup money for the present-day KAPIOLANI CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL (1890). Following Annexation, the deposed queen, Liliuokalani, placed her lands in a trust, resulting in development of an agency dedicated to the support of orphans and half-orphans. This is today’s QUEEN LILIUOKALANI CHILDREN'S CENTER.

The HAWAII OF KAMEHAMEHA was confronted with the devastating impact of contact with the outside world. Epidemics of previously unknown diseases, such as smallpox and measles, set the stage for our historical definition of philanthropy. Where the high alii and the monarchs of the Hawaiian Kingdom might have passed their assets to family members or retainers, they instead addressed their resources to health care, child care, education, and support of the elderly. For example, Queen Emma, in collaboration with her husband Kamehameha IV, raised the initial funds to launch the present-day QUEEN'S HOSPITAL (1860). William Lunalilo, the sixth Hawaiian monarch, willed lands for the creation of LUNALILO HOME for the elderly (1877). Queen Kapiolani, wife of the seventh monarch, Kalākaua, raised the startup money for the present-day KAPIOLANI CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL (1890). Following Annexation, the deposed queen, Liliuokalani, placed her lands in a trust, resulting in development of an agency dedicated to the support of orphans and half-orphans. This is today’s QUEEN LILIUOKALANI CHILDREN'S CENTER.

In a singular act of generosity, Princess Pauahi willed 375,000 acres of Kamehameha family lands for the formation of KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS in 1887. Her husband, businessman Charles Reed Bishop, endowed BISHOP MUSEUM as a means of perpetuating the memory of Pauahi and preserving the material culture of the Hawaiian people.

By such monumental acts as these, the idea of giving in perpetuity took on forms that, then and now, improve the lives of person after person, family after family, and community after community.

Christian Missionary Culture

The second big root of philanthropy grew from the the Christian missionary culture. At the intersection of the Hawaiian and Christian tradition, Kamehameha III prompted the mission to establish a school for ali‘i children . Amos Starr Cooke and his wife, Juliette Montague Cooke, opened their house in 1839 to what became known as the CHIEF'S CHILDREN'S SCHOOL. The school educated the last five of Hawaii’s eight monarchs, as well as Princess Pauahi and others key figures of history.

King Kalakaua (a graduate of the Chief's Children's School) and staff on Iolani Palace steps. Left to right: James H. Boyd, Col. Curtis P. Iaukea, Chas. H. Judd, Edward W. Purvis, King Kalakaua, George W. MacFarlane, Governor John Owen Dominis, A. B. Hayley, John D. Holt and Antone Rosa. J.J. Williams [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The early conduct of philanthropy was often framed by the Christian concept of charity, or the performance of good works. Pauahi herself was active with the missionaries in what is apparently the first social service project, the STRANGERS' FRIENDS SOCIETY. According to the social worker Margaret Catton’s voluminous account, Social Service in Hawaii, the Society was organized in 1852 and endured for more than a century. It was dedicated to addressing the indigence and drunkenness of passing sailors.

Hawaiian Humane Society

In a next step in social service, the HAWAIIAN HUMANE SOCIETY was organized in 1883. In addition to its compassion for animals, its mission statement expressed a concern for the well-being of children. Only in 1913 did human hunger, poverty and homelessness become a serious priority, roughly coinciding with the displacement of horses by motor vehicles. A wealthy part-Hawaiian woman, Lucy K. Ward, spoke Hawaiian, and over half of her clients were Hawaiian. She served as the Humane Society’s staff for the next twenty years, with a primary emphasis on the needs of children.

Ethnic Organizations

During this period, charity was often organized narrowly by ethnic group. The 1899 Thrum’s Almanac recorded one of the Big Five companies handing out grants of a thousand dollars apiece to the GERMAN BENEVOLENT SOCIETY, the BRITISH BENEVOLENT SOCIETY, THE LADIES PORTUGUESE CHARITABLE ASSOCIATION, the AMERICAN RELIEF FUND, the HAWAIIAN RELIEF FUND, CHINESE HOSPITAL and the JAPANESE BENEVOLENT SOCIETY.

Among the ethnic groups originally brought in as plantation labor, Chinese immigrants, as the first to arrive, were the first to establish self-help of a philanthropic nature. At the time, China did not have a consulate in Hawaii, so its immigrants were particularly vulnerable. After completing their labor contracts, Chinese workers gravitated to the towns or to Honolulu. They organized societies according to clan membership, dialect, or region of origin. The Chinese societies, several of which are still visible today, bought large houses that provided the old and poor with a free roof and dry bed. Otherwise, according to Catton, “Shopkeepers in Chinatown would dip from bags, open for display, a measure of rice for these passing beggars. Chinese restaurants gave them leftovers and allowed them to forage in the garbage.”

Chinese Christian churches opened settlement-house projects in Chinatown, as well as the earliest ethnic YMCA. The PALOLO CHINESE HOME opened in 1920. It initially served aged plantation workers, and today it continues its work by serving a much wider range of the elderly.

Chinese Christian churches opened settlement-house projects in Chinatown, as well as the earliest ethnic YMCA. The PALOLO CHINESE HOME opened in 1920. It initially served aged plantation workers, and today it continues its work by serving a much wider range of the elderly.

LARGE-SCALE JAPANESE IMMIGRATION followed Chinese immigration by more than three decades, with the first large groups of contracted workers arriving in 1885. Most were able-bodied young men who worked on the plantations, but an ethnic enclave comprised mainly of Japanese quickly grew up on the Ewa side of Chinatown. When the bubonic plague struck Honolulu in 1900, the houses of victims were torched by order of the Board of Health of the new colonial government of the Territory of Hawaii. Among those displaced by the runaway fire were thirty-five hundred Japanese.

It was then that the Japanese community formed its own benevolent society, which developed the Japanese Hospital. This was the original version of today’s KUAKINI HOSPITAL and its associated home for elderly Japanese.

The idea of self-help continued in later-arriving ethnic groups. Koreans, for example, established a home for their elderly. But as a generalization, ethnically based charity incrementally gave way to a philanthropy supporting community-wide goals.

Kindergarten Movement

The kindergarten movement of the early 1890s was a prime example of an inclusive effort. Hawai‘i’s first kindergarten was built in 1892 for the Chinese of Chinatown under the leadership of Francis Damon, a son of the seaman’s missionary Samuel C. Damon. Kindergartens for Hawaiian, Japanese, Portuguese and haole children quickly followed. By 1897, a visiting home nurse was added to this network, giving counsel and support to destitute families.

The philosophical base of kindergartens developed in Hawaii through contacts made by Henry Castle, a scholarly son of the early missionaries Samuel N. and Mary Castle. In his college studies, Henry became a friend and colleague of several of the leading American progressives of the period. En route home to Hawai‘i, he drowned at sea. His sister, Harriet Castle, inspired by his work, seized on her brother’s progressive ideas about education, as well as his acquaintances.

She brought the foremost educational philosopher of the day, John Dewey, to Hawai‘i for a series of lectures and a sharing of ideas. With money from their waterfront- and sugar-based corporation, Castle & Cooke, the Castles formed a family foundation that arguably was one of the first American foundations. Through her consistent effort, Harriet Castle led what became today’s KINDERGARTEN AND CHILDREN'S AID ASSOCIATION (KCAA).

A second offspring, Helen Castle, became an intimate of Jane Addams, founder of Chicago’s historic Hull House. As John Dewey was to progressive education, Addams was to the development of multipurpose settlement houses. These were dedicated to the nurturing of children and the multidisciplinary delivery of social services. Borrowing from the Hull House model, the renowned Palama Settlement House was formed, as were smaller “settlement” projects in other parts of the islands.

Left to right: Frank C. Atherton, Portrait of Anna Rice Cooke by Frederic Yates, Portrait of Emma Kauikeolani Wilcox by Charles W. Bartlett, Photo and portraits [pubic domain] via Wikimedia Commons

All of this was faithfully recorded by the contemporary historian Alfred L. Castle, who administers the present-day Samuel N. and Mary Castle Foundation. As a keeper of both history and tradition, Al Castle is known for consistently supporting the expansion of early childhood education.

World War I

Longtime mainstays of philanthropy such as the COOKE, ATHERTON AND WILCOX FAMILY FOUNDATIONS were formed in a wave of community-building sentiment that swept through Hawai‘i around the time of World War I. The first Wilcox Foundation of Kaua‘i was formed in 1915. The Cooke Family Foundation was formed in 1920, and the Atherton Foundation in 1921. The businessman Charles M. Cooke, son of the original missionaries, and his wife Anna Rice Cooke, became avid collectors of Asian as well as Western art. Eventually Anna turned over not only the family collection but the family home on Beretania Street to serve what is today the HONOLULU ART MUSEUM.

The transition of missionary families into a business elite, organized around the Big Five corporations, was to become a staple of Island history. Al Castle, for example, took note of the allegation that “philanthropy substituted for wholesale social justice in the Territory.”

“Whereas philanthropy modified the ills of an unjust social system, it did not fundamentally alter income and occupational inequities,” Castle wrote. “Indeed, critics of philanthropy in general have seen paternalism in the efforts of funders to reinforce social, economic and educational structure and institutions which ensured that a world favorable to a funders’ interest would be maintained.”

“Whereas philanthropy modified the ills of an unjust social system, it did not fundamentally alter income and occupational inequities,” Castle wrote. “Indeed, critics of philanthropy in general have seen paternalism in the efforts of funders to reinforce social, economic and educational structure and institutions which ensured that a world favorable to a funders’ interest would be maintained.”

Less discussed from this period, roughly a century ago, was a burgeoning of philanthropy in the missionary tradition that made Hawai‘i a more inclusive place. To complement the Territorial government’s public schools and the University of Hawai‘i, the missionary foundations quietly supported programs that served the goals of inclusivity and community-building. Perhaps the most ubiquitous and effective was the YOUNG MEN'S AND YOUNG WOMEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS. From the roots of the “Y” in Chinatown, the YMCA and YWCA flourished throughout the Territory in the 1920s and 1930s on a scale we find difficult to imagine today.

It particularly thrived in the inner city of Honolulu. In 1921, the Nu‘uanu YMCA organized an interracial board of directors. It phased out its separate Japanese, Chinese, and Korean YMCAs. By 1930, ethnic “guidelines” were abandoned. Youth workers such as John Young and Hung Wai Ching organized thousands of young people into clubs that stressed a combination of public service and physical fitness. Honolulu had more ‘Y’ members per thousand than any city of its comparable size in the USA, causing a visiting executive to exclaim, “There is more ‘Y’ work per square foot on Oahu than any other place I know of in the world.”

By focusing questions of human well-being, philanthropy stimulated reform movements that created pressure on government to address social ills.

The more elemental the problem, the more starkly true this was. Almost immediately after the Annexation, leading annexationists formed an entity called ASSOCIATED CHARITIES. At the time the benevolent societies—the Germans, the British, the Americans, etc.—were beset by roving beggars, who moved from one to another society asking for help. Associated Charities screened these individuals in an attempt to prevent duplication of charitable giving. It doubled as a job finder, placing male applicants in work as laborers and female applicants in work as washerwomen and domestics. Associated Charities had one staff member, who opened the door to the needy in the morning and rode through the city in the afternoon making home visits.

Sanford Dole, the first governor of the Territory, saw the limits of such a system. “Until pauperism is taken up on other grounds than philanthropy or charity, there seems little hope for its final suppression…” he wrote. Rather, poverty would only be successfully dealt with when “governments become alive to its importance as a national question deeply affecting their own strength and prestige.”

Twenty years after its inception, Associated Charities was renamed the UNITED WELFARE FUND, which advocated for the earliest form of government welfare payments. These became known as “Mother’s Pensions,” given to impoverished mothers, pregnant women and children. As part of the first welfare program, a single “housekeeper” began working with the poor in their homes, providing guidance in hygiene, diet, and clothing.

Great Depression

While the Great Depression is often described as having little effect on Hawaii’s plantation-dominated economy, the stories of people at the bottom of society’s ladder say otherwise. “Thus far,” a 1929 report said, “food has been supplied as sparingly as possible to prevent starvation and every effort has been made to find work.” The previously meager welfare allotments were cut further to spread them more widely.

To minimize unemployment, the plantations shipped thousands of Filipino workers back to the Philippines, some of them as deportations without consent. Aged and unemployed workers made up more than half of all the indigent. In response, in 1933, four years into the financial crisis, the Territorial Government passed an Old Age Pension Law, which was restricted to U.S. citizens. This was at a point when large numbers of people were immigrant aliens and were, therefore, ineligible for the law’s benefits. After another four years, the Territory created a Public Welfare Department to qualify for distribution of Federal social security funds.

“Voluntary organizations everywhere were taking stock; realizing in the process that no longer was their clientele composed exclusively of the chronically indigent—the ‘charity cases’—begging for food, shelter, and clothing,” Catton wrote. “Their caseload now included the educated and the intellectual, the professional person and the skilled artisan, forced by the Depression into want.”

Castle agreed: “In Hawaii as well as the rest of the nation, the Great Depression permanently changed the alignment between public and private social service providers. Because the private sector was unable to deal with the extraordinary volume of human need, the burden of providing these services was transferred to territorial, state, local and federal governments.”

Courtesy of Palama Settlement Archives

World War II

Following World War II, spending on welfare and social services grew four times faster in the public sector than the private sector. By the 1980s the ratio of public to private spending in these areas was ten to one.

Health care was especially slow to materialize. The Territorial Government opened a dispensary in Honolulu in 1905 between the hours of eight a.m. and nine a.m. If the doctor was inspecting a ship in port, the dispensary would close altogether. In 1915, the dispensary was transferred to PALAMA SETTLEMENT and continued there until 1947. During this time, QUEEN'S HOSPITAL provided free hospitalization to low-income people on a limited basis.

Health care only changed significantly with the development of unionized negotiations and group plans through the Hawaii Medical Services Association and Kaiser Health Plan; and finally with legislative passage of the Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act of 1974, which resulted in Hawai‘i having the highest percentage of people insured for medical care in the United States.

AS ALL OF THIS ILLUSTRATES, philanthropy in Hawaii is bound up in complex social and political history. There are distinct whole chapters for each of the world wars, the battle for unionization of workers, the rise of the Democratic Party, and the transition to Statehood.

Greatly simplified, this history is about transitions from ethnic concern to community concern, and from private beneficence to public entitlement.

Nonetheless, private philanthropy is more widely practiced than ever. A social worker framed contemporary philanthropy as follows: “Charity used to be the ‘cake’ for the poor. Now government does the basics, and philanthropy is the icing on the cake."

Private philanthropy is spread in all manner of ways—as a community kitchen, as a response to a typhoon in the Philippines—but it tends to aggregate resources toward two ends. One is to create efficiencies that stretch society’s capital. The second is to strategically identify society’s most pivotal problems, so as to map a way forward.

The Hawaii Community Foundation

THE HAWAIIAN Foundation (HF), predecessor to today’s Hawaii Community Foundation (HCF), was formed a century ago, in 1916, incrementally encompassing the goals of efficiency and strategic focus. The original funding was quasi-governmental, generated by unclaimed deposits left in banks by persons who died without a will.

THE HAWAIIAN Foundation (HF), predecessor to today’s Hawaii Community Foundation (HCF), was formed a century ago, in 1916, incrementally encompassing the goals of efficiency and strategic focus. The original funding was quasi-governmental, generated by unclaimed deposits left in banks by persons who died without a will.

Slowly, the Hawaiian Foundation became a repository for people who wished to give or leave behind their resources for a broad public purpose. Accordingly, a 1923 gift by a Ruth Makee Tenney for the general purposes of education, science, research, health care and improvement of living conditions “regardless of race, creed or color” is the first marker celebrated in the HCF timeline. The first scholarship fund was awarded in 1931.

A 1969 reform of the U.S. tax code governing philanthropy led to a much more broadly-based system. The original foundation was managed by Hawaiian Trust Company and Bank of Hawai‘i. It became a community trust in 1987, significantly changing its name from the Hawaiian Foundation to the Hawaii Community Foundation. The Board of Governors expanded and diversified, and the trustee base was broadened to include First Hawaiian Bank, Central Pacific Bank, and the Bishop Trust Company. What this did, effectively, was to create a more diverse range of doorways through which people could explore the ideas of giving away their resources in perpetuity.

Public-interest philanthropy began to grow steadily. ROBERT BLACK bequeathed shares in E.E. Black Construction Company to the Hawaii Community Foundation valued at $60 million. There have been other large gifts since, such as $40 million by the JACK LORD ESTATE and $50 million from PIERRE AND PAM OMIDYAR. However, the majority of HCF assets, currently $543 million, reflect the accounts of seven hundred smaller funds.

Public-interest philanthropy began to grow steadily. ROBERT BLACK bequeathed shares in E.E. Black Construction Company to the Hawaii Community Foundation valued at $60 million. There have been other large gifts since, such as $40 million by the JACK LORD ESTATE and $50 million from PIERRE AND PAM OMIDYAR. However, the majority of HCF assets, currently $543 million, reflect the accounts of seven hundred smaller funds.

Toward the goal of making specific-purpose gifts more efficient, HCF in the year 2000 began computerizing applications for academic scholarships. Within a decade not only the number but the dollar value of scholarships had tripled, and the number of applicants had multiplied five times over.

HCF - Environment

Beginning in 1999, HCF launched a major initiative in environmental grant-making. Because Hawai‘i’s landscape is so diverse, segmented, and fragile, it is literally the species extinction capital of the world. Perhaps in the Twenty-first Century, partly through the involvement of HCF, Hawai‘i may become the species preservation capital of the world.

HCF initially helped build a network of watershed partnerships and land trusts. It was particularly concerned with combatting the spread of alien species and managing watersheds. More recently, HCF has helped seed community-based marine conservation programs throughout the islands.

HCF is also engaged in the issues of climate change. Its FRESH WATER INITIATIVE is aimed at water security in an era of rising ocean waters. Through a Community Restoration Partnership, it is encouraging communities to counter the loss of habitat by managing entire ahupua‘a, from mountain peaks into the surrounding seas.

HCF is working to preserve watersheds and combat climate change

HCF also serves as a source of philanthropic knowledge for others. For example, it nurtures a growing ENVIRONMENTAL FUNDERS GROUP. It now has fifteen members, who meet monthly to discuss sustainability and environmental threats.

Initially, inclusion of environmental programs in the work of HCF caused a tremor of apprehension among traditional grantees for health, education and welfare. Such concerns were allayed by development of a five-year partnership beginning in 1999 with the California-based Hewlett Foundation and Packard Foundation, both of which were interested in protecting the unique ecology of Hawai‘i. Since then, environmental funding has grown overall, and environmental grants are nearly one tenth of HCF giving.

HCF- Education

Innovation in education is a consistently high priority of HCF, expressed through a variety of grants and initiatives. One is called SCHOOLS OF THE FUTURE. It is designed to give teachers and administrators time to step back from the grind of their tasks, to talk, and to think. Initially focused on the educational possibilities of digitization, the initiative quickly developed into gearing students for the 21st century. This became a self-sustaining annual conference, most recently attracting two thousand teachers.

Through CONNECTING FOR SUCCESS, HCF brought a group of thirteen funders together to concentrate support for vulnerable middle-school students at risk of dropping out of school. The premise of this project was to identify and nurture at-risk students while they are still receptive to help.

With increasing frequency, HCF serves as a conduit for receiving and relaying the public response to tragedy.

DESPITE THE COMBINED EFFORTS of government investment and private philanthropy, the framework of history readily reminds us of challenges the community strains to meet or is either unable or unwilling to meet. In that light, today’s philanthropy either can be interpreted as a leap of progress or a nagging reminder that the essential problems of society of one hundred years ago have not been solved.

Where relief supplies once were stockpiled in the Throne Room of the Palace, contributions come in from donors and go out to those in need almost instantaneously by computer.

In all, roughly one third of HCF’s annual distribution goes to human services (including health), one fourth to education, and one tenth each to the arts, community development and the environment.

As a means of fostering reflection, centennials are curiously useful. Where kindergartens were a pioneering philanthropic project, as a society we have yet to finance an early childhood program for all. Where a single doctor once answered to indigents between eight and nine in the morning, the medical care and hospital budgets of State government are bursting. Where we once planted trees to beautify the commons, today we face the cascading problems of alien invaders, watershed degradation, sea-level rise, and global warming.

There is a bright side. An essayist on the future of philanthropy predicts that more rapid and widespread communication will “accelerate, extend, blur and enhance participation.” To this she adds, “We can identify and notify other people more quickly about emerging problems; we can respond more rapidly to acute crises; and we can gather and distribute resources much more easily, efficiently, and quickly.”

In our lifetimes, certainly in the past one hundred years, we have witnessed a dramatic expansion of giving.

We have solved problems that were seemingly intractable. We have evolved from narrowly focused charity work to broadly focused community work. We are developing a culture of philanthropy that includes practically everyone across the board.

HCF’s periodic GIVING STUDY produced the figure of ninety-three percent participation in some form of giving. It is a number that encourages the idea that “giving back” to one’s community of interest is part of human nature. To be fully human is to help other humans. From the renowned biologist E.O. Wilson’s study of ants, bees, termites, wolves and humans, he concluded that only a handful of the earth’s species have crossed the line into “eusociality,” of which the distinguishing feature is concern for, and devotion to, something outside of one’s self. He uses the word “altruism.”

Hawaii is a frontier of giving not only to those who live next door who are like us, but rather to humanity in general.

Consciously or unconsciously, every one of us does render some service or other. If we cultivate the habit of doing this service deliberately, our desire for service will steadily grow stronger and we will make not only our own happiness, but that of the world at large.

- Ghandi

Possibly this is cultural evolution. Possibly as we scurry to keep pace, we may pause a moment to celebrate our progress.

|

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Coffman's writing and films are about the social and political development of Hawaii in the context of the Pacific Rim. After working briefly as a community liason for the Honolulu Community Action Program, he was chief political reporter of the Honolulu Star Bulletin (1968-73). He since has been an independent writer and producer.

His Catch a Wave, about contemporary politics, sold out five thousand copies in a week and went through five printings.He is the recipient of the State of Hawaii Literary Award, and three of his books received the Hawaii Publishers' annual award for Best Nonfiction: Nation Within, The History of America's Occupation of Hawaii; The Island Edge of America; and I Respectfully Dissent; A Biography of Edward H. Nakamura. His most recent book, How Hawaii Changed America: The Movement for Racial Equality, 1939-1942 attempts to trace the roots of contemporary Hawaii.

|